People will keep saying that some plant species or other was originally described or published in Linnaeus’s Species Plantarum of 1753. They even do it when it’s the kind of plant whose ocean-going seeds have established it on more of the planet’s warmer beaches than not, as Ipomoea pes-caprae‘s have:

Even allowing for eurocentrism on the part of the author above, most of those beaches had been frequented by Europeans, including plant-describers, rather earlier than 1753. In the last two posts (here and here) I pointed out that Species Plantarum rarely describes species in any meaningful sense of the word at all or publishes them first. What it does do is classify species differently from earlier works and differently, also, from the way in which we classify them today.

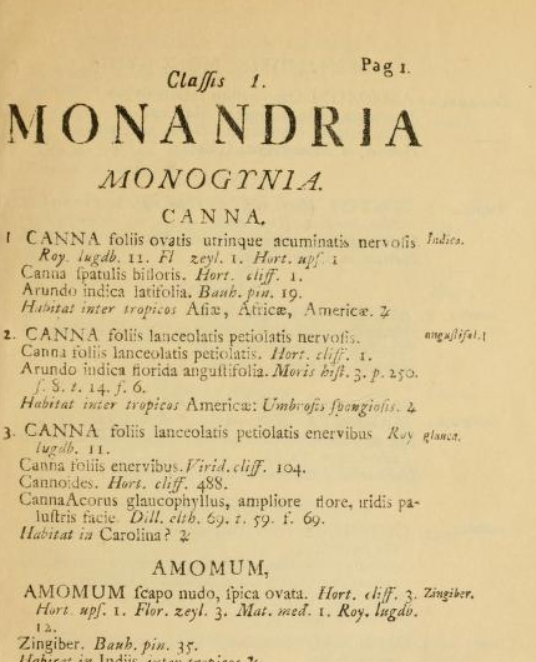

The basic plan can be grasped from page 1 of Species Plantarum. Here, we are confronted with the massive heading Monandria, the first class or level, containing plants with one male part in their flowers. Class 2 is reserved for flowering plants with 2 male parts, the Diandria, then the Triandria, you get the picture… The next organisational level, the order, which is in smaller type, is based on the number of female parts, first the Monogynia, then the Digynia. So every species in Species Plantarum is classified based on the number and organisation of its male and female parts.

Having exhausted the sexual arrangements of species with hermaphroditic flowers, Linnaeus moved on to those which produce separate male and female flowers, then the Cryptogams, whose means of producing gametes, if any, were cryptic.

The next heading in position and size and next level of classification is the genus. At the top of the page above, we have the Canna, and lower down on the same page, the Amomums. The name of each species in Linnaeus’s text is made by combining the genus with the species epithet appearing in the margin. The name of the first species in Species Plantarum is Canna Indica, the Indian Shot, whose flower has one stamen (male part) and one pistil (female part).

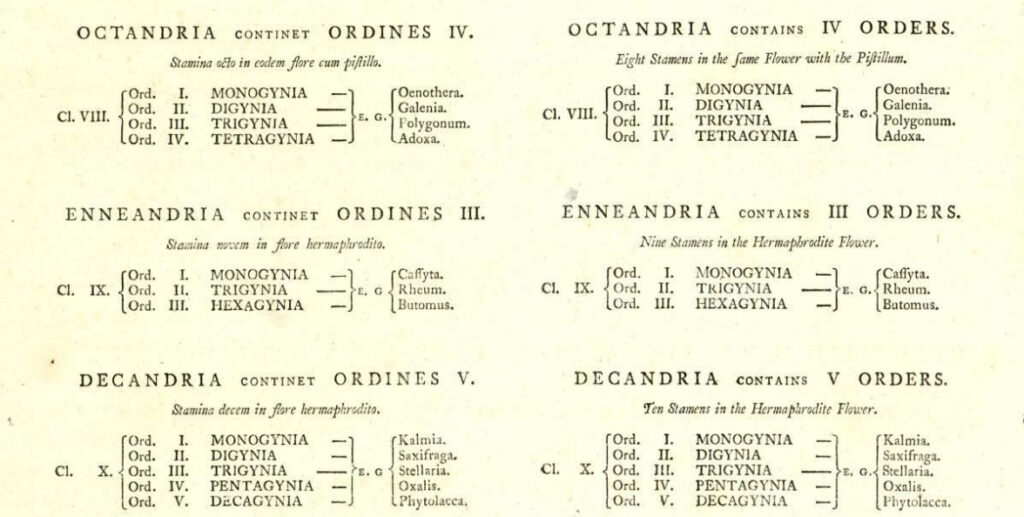

It might have been nice if Linnaeus had included a handy table of contents with an overview of his system and perhaps some diagrams. Genera Plantarum of 1737 is rather more explicit, but it still doesn’t achieve the down to earth clarity of the synthesis by Johannes Sebastian Müller, aka John Miller. John Miller was a German-born engraver who emigrated to England, changed his name, and worked at the Chelsea Physic Garden at a time when the head gardener was Philip Miller (no relation). Despite the confusion this might entail, John Miller believed in clarity where Linnaeus’s system was concerned and did his best to increase it. Here is just a taster from his table of the classification system in Illustratio Systematis Sexualis Linnaei of 1770, almost superfluously bilingual, in Latin and English:

Botanical science has not used Linnaeus’s plant classification system for some time although it retains and attaches importance to the binomial naming system. For some time after the publication of Species Plantarum however, the reverse was the case: it was Linnaeus’s proposal of classifying plants by sex which seemed most important. There were probably many reasons for this, but I will try to give a few particularly heuristic ones.

If you have 6000 or 7000 plants to organise in a book or herbarium, you are going to need to break them up into groups and order them somehow. Linnaeus’s system offered the following advantages:

- A way of organising plants that rests in the plant itself rather than in any vagaries of human culture such as naming or utility. This is part of what is meant by saying that botany became phytocentric – although it is also part of what is meant by saying that it decontextualises plants. It is also a rather clever trick to make plants themselves supply the index to the botanists’ books.

- A basis in plant features which were discrete rather than variable, could be counted rather than needing to be described, and could therefore command universal agreement. Ask people to state the colour of a petal or the form of a leaf, and you are quite likely to receive varying answers. With the sexual system, anyone who could recognise the male and female parts of flowers could count them and reach the same answer as anyone else.

- A choice of system which, when applied to those 6000 or 7000 plant species, broke them up into a reasonable number of reasonably-sized chunks. It was a matter of good fortune for Linnaeus and his immediate successors that the variety of sexual arrangements among plants known at the time was well suited to this task.

The result was, at least in theory, that a person applying this system to a plant in the field could easily discover where (or whether) it appears in the publication of any botanist applying the system, even if the two of them were separated by half a planet, a hundred years, or nations at war. Like most theories, this one developed issues where the rubber hit the road. Beginners struggled to apply it at all. Since few plants flower all the time, everyone depended on fortunate timing. Taking flowers apart in order to observe their reproductive parts was perhaps not over-burdensome, but for the first time, a good magnifying glass became a necessity.

John Miller aimed to at least help beginners identify male and female organs in flowers and provided careful diagrams of floral structures across the Linnaean classification system. His Turnera ulmifolia , shown below, was in the Pentandria class (5 stamens) and the Trigynia order (3 pistils).

While ever the sexual system dominated plant classification, botanical illustrations displayed a similarly detailed attention to diagramming dissected flowers. They emphasised traits which are not always easy to spot in real life, certainly at a casual glance. Turnera ulmifolia, often called Yellow Alder, and sometimes West Indian Holly though it is also Central American, has an open corolla which means that the arrangement of stamens and pistils can be appreciated from a sufficiently blown up photograph. Many flowers take a more modest approach.

Much was said in the past, concerning the advantages and disadvantages of Linnaeus’s sexual system. Because humans can hardly prevent themselves from anthropomorphising, it was not all of a scientific nature. Perhaps, it didn’t help that the lines between botany as science and as hobby very blurred. More recently I have heard it said that the age which produced full-on libertine pornography and titillating Gothic villains and heroines was shocked by the topic of plant sex. It is perhaps more likely that it offered some of them a new opportunity to be ‘shocking’, albeit in a more low-key way than some of their contemporaries.

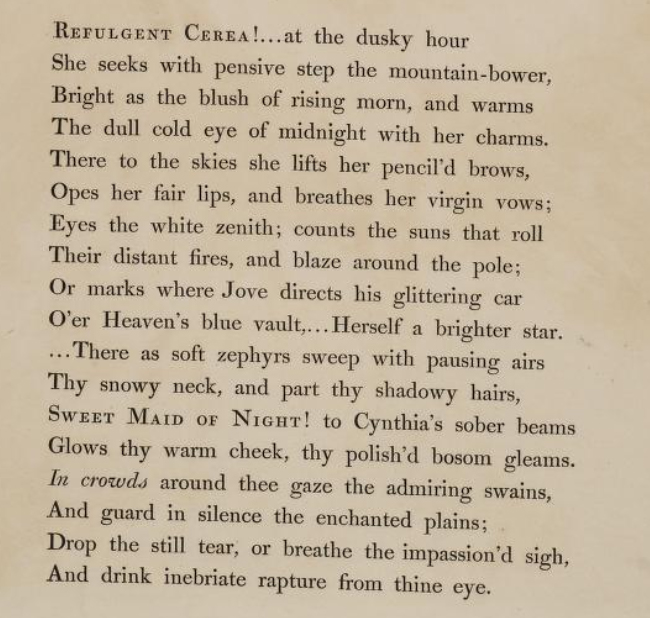

To the interested public, the sexual aspect of Linnaeus’s system was both feature and bug. In hindsight, one of its greater crimes is giving to Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles, the occasion to write poetry. I have always thought of Charles Darwin as a plodding but necessary writer. I now see that that literary talent improved as it passed down the generations. Here is how Grandpa Darwin let himself go on the subject of an unfortunate epiphytic cactus now named Selenicereus grandiflorus or Queen of the Night:

At least the word ‘refulgent’, which means ‘burning brightly’, is good for a laugh!

This specimen of literature was first published in something called Loves of the Plants but I came across it in an even odder book called Temple of Flora, published in 1807 by Robert John Thornton. Thornton seems to have intended to update Miller, but his Temple is rather a different animal. It includes, alongside very expensive flower illustrations, a great many poems by Erasmus Darwin and other rhyme-botherers of a similar ilk, a calendrical medley of European flower folklore, a defence of horticultural hybrids, a diatribe against war, a commentary on Linnaeus with scientific pretensions which goes well out of its way to deploy sexualised vocabulary, some gratified acknowledgement of Britain’s latest military successes, an overview of the Eastern religions for people who know nothing about them by a person who knew only a little bit more, a Gothic section for plants which involve themselves in activities such as blooming at night, consuming insects, or smelling of corpses…

It is in this section that the Queen of the Night finds herself. Notwithstanding her origin in the West Indies and Central America (just like Turnera ulmifolia) Thornton sets her against a European-looking moonlit church, albeit one which I suspect is supposed to evoke southern Europe as much as the British Isles.

Thornton was obviously striving to cash in on the Twilight effect of his day (by Twilight, I mean Stephenie Meyer’s teenage vampire romance series). In this attempt he failed, probably because teen girls of his era simply preferred Ann Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho to sexualised botany, possibly because, as he suggested himself, lavishly illustrated albums exceeded the disposable income of even those few who could afford books.

Like Thornton’s fortunes, Linnaeus’s system of sexual classification died a death. It is now nothing but a historical oddity, an abandoned gadget in the kitchen drawer of science, not as useful as it seemed at first and certainly no match for its modern replacements. It has nothing to do with the special status of Species Plantarum today, which itself has nothing to do with describing, and only a little to do with publishing.