In a previous post, I said that hardly any plants at all were first described in Linnaeus’s Species Plantarum. Instead, almost all its entries consist of bibliographic references. There were a few exceptions and in this post, I take a closer look at one of them.

Persicaria chinensis is the Chinese knotweed, a potentially rather invasive plant which likes to colonise patches of disturbed land. As its name suggests, it’s native to China and other parts of Asia as far west as India. Invasive or not, it hasn’t turned up in too many other parts of the world yet, but as of the beginning of the 20th century, Jamaica is one of them. So far, it doesn’t seem to have reached any of the other West Indian islands. On page 54 of a 1996 report mainly discussing Persicaria chinensis’s fellow invader, Pittosporum undulatum, Goodland & Healey say:

“P. chinense was probably introduced to Cinchona as it was collected from near there in 1905, by W. Harris, who described it as “rapidly spreading and becoming quite naturalised” (information from Institute of Jamaica herbarium).”

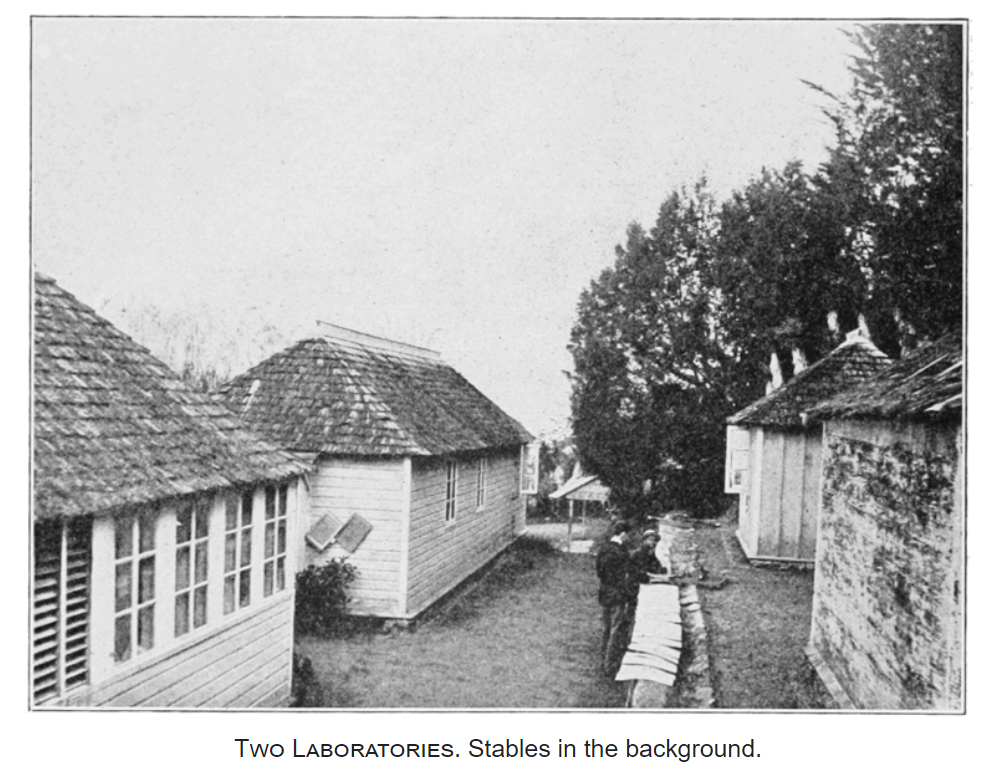

Cinchona Botanical Gardens are set high in the Blue Mountains of Jamaica where temperatures are cool. The image above shows two botanists working on specimen sheets outside the garden’s laboratories. William Harris, mentioned above, may have prepared his specimen of Persicaria chinensis in a very similar way. However, this image was published in 1914 as the British were regaining possession of Cinchona after a decade during which it was leased to American botanical institutions. My tentative guess is that the white man at work here is a visiting American botanist, while the black man is from Cinchona itself. Work at Cinchona depended on a Jamaican staff of gardeners, guides and caretakers, including David Emmanuel Watt, who managed the institution during the American lease.

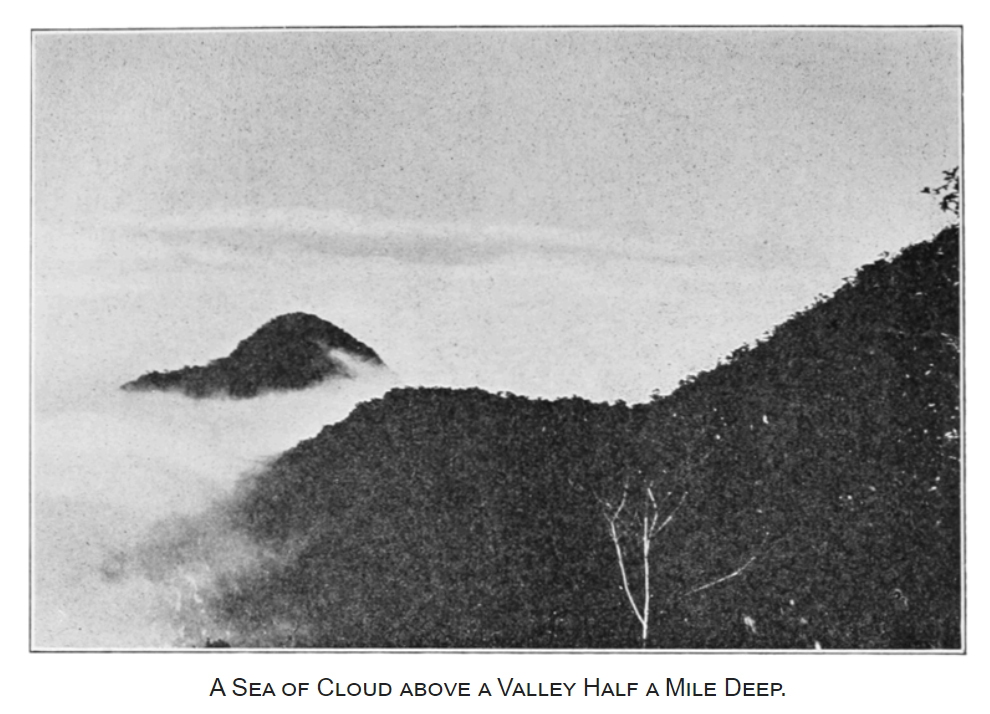

This image, from the same publication, shows a view from Cinchona over forested mountain slopes already colonised by Persicaria chinensis. Since at least 1886, Cinchona had been used by British government botanists for the acclimatisation of species from temperate regions. While there is no actual record of Cinchona botanists introducing Persicaria chinensis it is no surprise that Goodland & Healey suspect them. With the hindsight of the 21st century, it easy to wonder what would possess botanists, if they must introduce exotic species to an island at all, to pick a rather obviously invasive one. In fact, although they may have had reasonings, it’s also possible that Persicaria chinensis hitched a ride on the coat-tails of some other plant and showed up uninvited. It’s been there over a century now, although by 1996 it was clear how much of a threat it might pose to native species.

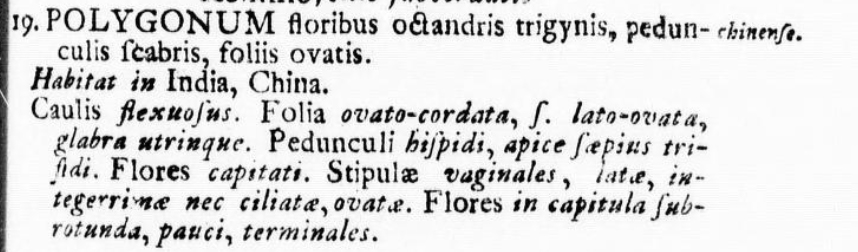

Written some 150 years before Persicaria chinensis reached the West Indies, Linnaeus’s entry in Species Plantarum looks like this (he calls it Polygonum chinense but it is the same species, known as Persicara from 1913):

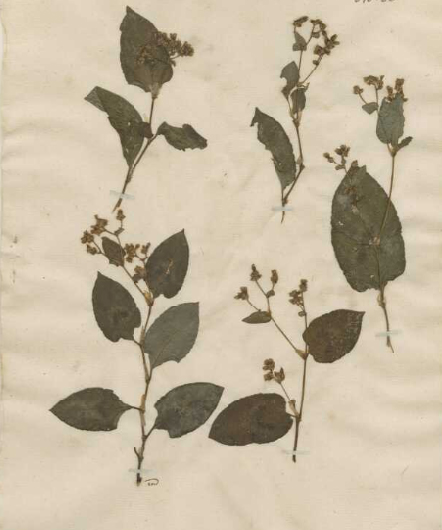

Here, a plant species really is being described in Species Plantarum. There are no references at all, just a text in Latin that tells us a bunch of rather technical things about the plant’s anatomy, for instance, that its leaves are glabrous and its peduncles hispid. In the last post, I translated (with help from Google) a Latin plant description of 1648 into perfectly colloquial English. By 1753, botanical vocabulary had developed to the extent that to the non-specialist, it might as well be an extract from Lewis Caroll’s Jabberwocky, regardless of the language. Aimed at specialists then, Linnaeus made this description, not from a living plant, but working, as usual for plant systematists, from a sheet in his herbarium. I am virtually certain that the collector and creator of these pressed specimens of Persicaria chinensis was his former student, Pehr Osbeck.

Pehr Osbeck was primarily a man of religion, who had taken Linnaeus’s university course in botany more or less as what we would call a minor, with theology as his major. Natural history remained his lifelong hobby, the priesthood was his profession. In that capacity, he got a job as chaplain on an 18-month long voyage to Canton in China with the Swedish East India Company. Many, though not all, of Linnaeus’s Asian specimens originate from this voyage. In 1757, four years after Species Plantarum came out, Osbeck published an account of his journey which includes an extract from his diary describing the collection of Persicaria chinensis. The English translation dates from over a decade later, and the relevant passage begins on p.325 of Volume 1.

On 8 September 1751, Osbeck had taken a Sunday afternoon outing to what appears to have been a temple complex in a town across the river from Canton. The afternoon was spent with a group of unspecified people, probably his fellow Swedes, who seemed willing to humour his interest in plant-collecting up to a point. Still, it was only when they visited the cemetery that he was relatively successful in collecting specimens:

“We went through the little wood of Bamboo trees, and came to a high even spot, where the Chinese buried their dead. Some coffins stood above the ground, and were put close to the trees like bee-hives. They occasioned a stench which made me keep off. In this manner they bury those whose kindred is either unknown, or who come from very distant parts. In the burying place I found: …”

And there follows a long list of plants including Polygonum chinense, as Linnaeus called it. A cemetery is not a surprising place to find a species which specialises in colonising disturbed ground. Its plants may have been wild, in the sense that they were self-seeded and growing in free competition without human intervention, but the space itself is anthropogenic and favours particular types of plants. The context in which Osbeck was able to collect coincided with these subsets of species.

Most Species Plantarum entries generate chains of references we can follow backwards in time. The one for Persicaria chinensis is the root of a new chain in Europe. We might reasonably suspect the species has an older publication history in Asia but Osbeck’s ability to interact with Cantonese people and culture was very limited. He became a vehicle for transmission of knowledge of the plant, via a small group of preserved individual members of its species, but not about the plant. His book only reports a transcription of its local Cantonese name: Ka-yong-moea. By the mid-18th century, when Species Plantarum was published, Europeans and Asians were influencing each other in many ways. In some contexts, this involved exchanges of medical and cultural information, botanical texts, and living plants. Nevertheless, it seems that Asian texts did not become physically or linguistically accessible to Linnaeus. Unable to cross-reference the two traditions in the way he was referencing European texts, he began a new textual sequence.

One of the wonders of the 21st century is that now, even someone with no detailed knowledge of Asian botanical history and a pre-Kindergarten level-grasp of Chinese characters (someone like me) can learn in just a few minutes that Persicaria chinensis is known in Mandarin as 火炭母 (Fo Tan Mu) which translates well enough as Charcoal Motherwort, and that it was first recorded in the Ben Cao Tu Jing (圖經本草) of 1061. As far as I know this was its earliest description and publication.

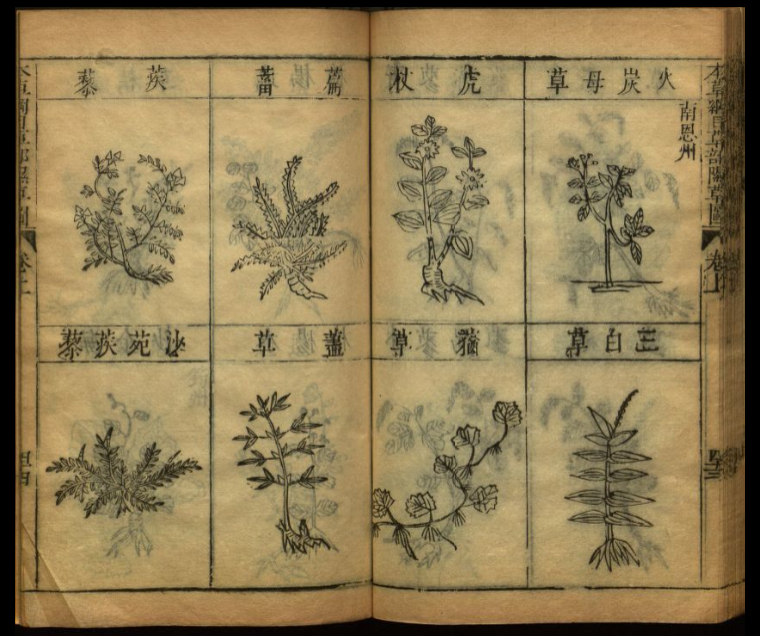

The Ben Cao Tu Jing, or Illustrated Classic of Materia Medica, was the result of a Song dynasty government project to compile all the materia medica used throughout the land. It was intended as an update of the much earlier Shennong Ben Cao Jing attributed to the legendary Shennong, in which Persicaria chinensis does not seem to be present. For the Ben Cao Tu Jing, officials sent details and samples back to court where the information was compiled under the leadership of court scholar and scientist Su Song. As the title suggests, the book included small woodcut images of many of the plants. There appear to be no surviving copies of the original text but it is supposed to have been copied and enlarged upon by Li Shizhen in the Ben Cao Gang Mu of the 1590s. (See here for a Wikisource machine-readable version).

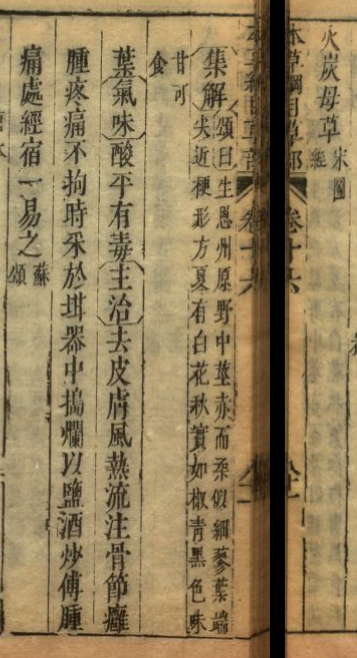

Li Shizhen was a physician of the Ming Dynasty who seems to have largely bypassed the court system and acted, through most of his life, as an independent professional and scholar. He embarked on a vast project to systematize the medical knowledge of his time, relying primarily on a bibliography which, by many accounts, included 800 or 900 other texts, as well as his personal expertise as a physician and some knowledge collected on his travels. Unlike Species Plantarum, the Ben Cao Gang Mu recopies the information it references, allowing it to act as a stand-in rather than merely a reference. Li’s major contribution, other than collection, lay in the systematisation of a body of knowledge which had grown to the point of being unwieldy. There were various printings of this Compendium of Materia Medica. The one shown below dates from 1784. Because of the way it was scanned, the entry for Persicaria chinensis is spread over the far left of image 83 and far right of image 84 in Volume 20, but the two sections are brought together below (with many thanks to my daughter, a student of Japanese, for help in tracking down the entry through her knowledge of kanji):

This text says something like the following:

“Charcoal Motherwort (Song – Book of Images) [Collection] The Charcoal Motherwort grows in the wilderness of Nanzhou. Stems are red and non-woody, like other Polygonum spp. The leaves are tapered at the tip, square near the stem. It has white flowers in summer, and fruits like peppers in autumn. They are green and black, sweet and edible. [Odour] The leaves smell sour, flat and poisonous. [Application] To remove wind-heat on the skin, flow into the joints, carbuncles and pain. Crush it with salt and wine, apply it to the swollen and sore area, and change it every day. (Su Song).”

Li Szhichen’s Compendium also included separate volumes of woodcuts of the plants described. In this scanned edition, Persicaria chinensis appears in the top right corner of image 44 in Volume 1:

It follows that like most other plants in Species Plantarum, Persicaria chinensis had a publication history prior to 1753, in this case, a discontinuous one. There may be a very small number of exceptions even to this circumstance, involving plant specimens from regions without a textual tradition which happened to reach Linnaeus before anyone else. Perhaps I will go looking for one in a future post.

Out of about 6000 species listed in the Species Plantarum, there are just over 1000 with which I’m particularly concerned because they are seed plants currently present in the West Indies. Fewer than 20 of these 1000 entries consist of descriptions rather than references to earlier publications. If that proportion were to hold true for the rest of Species Plantarum, perhaps 2% of its entries might qualify as ‘original descriptions’. There are some reasons why the proportion might not hold true. An important one is that European plants are under-represented in my set of 1000. I believe they make up about half the entries in Species Plantarum and it seems possible that Linnaeus’s rate of new descriptions for European plants would be different. Whichever way you slice it, Species Plantarum is not even supposed to be a book in which plants are described and published for the first time.