Carl Linnaeus’s Species Plantarum of 1753 is well-known as a foundational publication in botany. It isn’t unusual to see it presented as a book in which plant species were first described or first published, as in the Wikipedia reference for Cucumis anguria shown above. In reality, very few species were originally described and published in Species Plantarum.

I might talk about the small number of exceptions in a future post. Cucumis anguria is not an exception. I’m taking Cucumis anguria as an example because it happened to fall in front of my eyes as I was thinking of writing this post, but this mistake, of supposing that plants in Species Plantarum were first described by Linnaeus, is rife on Wikipedia, in the popular imagination, and even in places where the authors really should know better. Let’s see what the actual publication and description history of this species is.

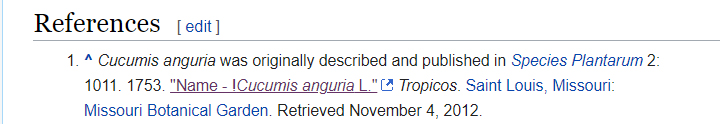

Cucumis anguria is one of many squash-type plants which produce an edible gourd. Its English names often compare it to cucumbers or gherkins. It comes from Central Africa and has been quite widely introduced to those parts of tropical America that were affected by the slave trade. I guess it has some potential as a garden plant although it also seems to get by quite well on its own. It has naturalized (gone wild) quite successfully in those parts of the Americas where it now lives. We can see the long term result in this distribution map, from Kew Gardens’ Plants of the World database:

Carl Linnaeus’s Species Plantarum is not primarily a book that aims to describe plants. Instead, it’s primarily a bibliographic index. It lists earlier published references for each plant, under a unique binomial name of the format now familiar to us. The first word of the name, ‘Cucumis’ in this case, is shared by a number of similar plants: other Cucumises such as the seven listed by Linnaeus. This first word is allowed to be arbitrary and often invokes some botanist or other although not in this case. The second word is often meaningful and related to the plant. In this case ‘anguria’ seems to be Ancient Greek for ‘cucumber’. It’s mostly the convenience of this naming system which is at the root of Species Plantarum‘s special status as a botanical text, not the originality of the content.

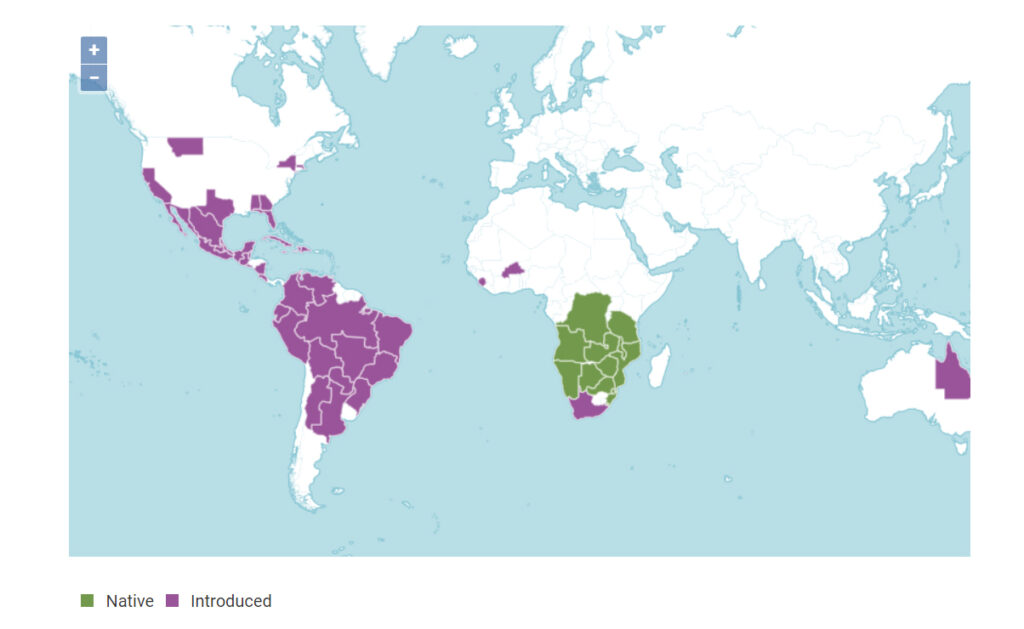

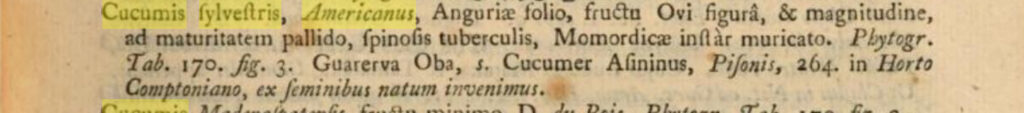

Linnaeus’s Species Plantarum entry for Cucumis anguria looks like this:

This is just a list of four references to earlier published works, with the author and title in abbreviated form and a page reference. All the other stuff in Latin is the ‘name’ given to Cucumis anguria in each of these earlier works. Some of these ‘names’ can come across a bit descriptive although they’re not quite full descriptions. These four books were published at a time when natural historians were referencing plants by abbreviated descriptions known as polynomials (many-word-names). They are given here for reference purposes. If we go to p.263 of the book listed here as Roy. Lugdb. there will be many entries, and the one we want will be for ‘Cucumis foliis palmatis.’

The four references Linnaeus cites for Cucumis anguria are:

- Hort. ups. – which is Linnaeus’s own Hortus upsaliensis of 1748.

- Roy. Lugdb. – which is Adriaan van Royen‘s Florae leydensis prodromus, sub-titled ‘exhibens plantas quae in Horto academico Lugduno-Batavo aluntur’ of 1740.

- Pluk. Phyt. – which is the 3rd volume of Leonard Plukenet’s Phytographia of 1692.

- Sloan jam. – which is Hans Sloane’s Catalogus Plantarum quae in Insula Jamaica of 1696.

We can also notice that Linnaeus says the plant lives in Jamaica. He doesn’t know it as an African plant but only through its introduction to the West Indies. Interestingly, he does say, on pp.292-3 of Hortus upsaliensis, that it bears a resemblance to another plant he had seen published as ‘Cucumereum africanum echinatum minorem‘ in Paul Hermann’s Paradisus Batavus of 1698, on p. 133 t. 133. This was a good intuition but Cucumis africanus did not appear in Species Plantarum and it would be too much of a detour to follow its publication trail just now. In Species Plantarum, Linnaeus says Cucumis anguria is Jamaican because, to his knowledge, that’s where the specimens and plants underlying these publications came from.

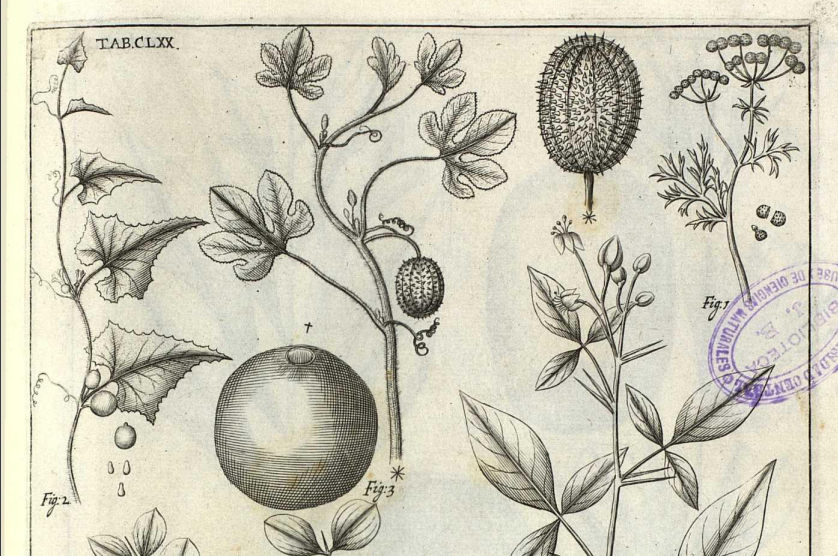

The earliest publication cited here by Linnaeus is Plukenet’s Phytographia. Plukenet was a Londoner who remained in Britain throughout a life much occupied with botanical matters. The reference is to this small picture, figure 3 in the middle of plate 170, nestling among many other, quite different plants:

The whole of Plukenet’s Phytographia consists of engravings of plants like this one. Some of them perhaps came from dried specimens, others from life. As it is quite hard to press a squash, let alone guess what it would look like afterwards, a drawing from life seems more probable. The caption for Plate 170 and Plukenet’s slightly earlier Almagestum Botanicum of 1693, p.123 confirm this:

The last line says a Cucumis anguria plant was grown from seeds in Compton’s garden. Henry Compton was the Bishop of London and an enthusiast of exotic plants with a garden at his residence of Fulham Palace. Who sent or brought him these particular seeds, I have not been able to find out nor can I guess. It could easily have been Hans Sloane, the author of the final book on Linnaeus’s list, but then again, there were quite a few other people it could have been. However, Sloane’s writings on Cucumis anguria, though they were published a few years after Plukenet’s, do help us extend its publication trail back a little further.

Hans Sloane was born in Ireland but spent most of his life in London. During his late 20s he spent a brief period in Jamaica as the private physician of the recently appointed governor. Although he didn’t manage to keep his employer alive for very long the trip led to a lasting association between himself and Jamaica. He returned to Britain with a contacts list which included a woman who would soon become a widow with a sizeable income derived from a slave plantation and then Sloane’s wife. This seems to have made a considerable contribution to his own wealth. In the meantime, he also brought back a quantity of notes and specimens.

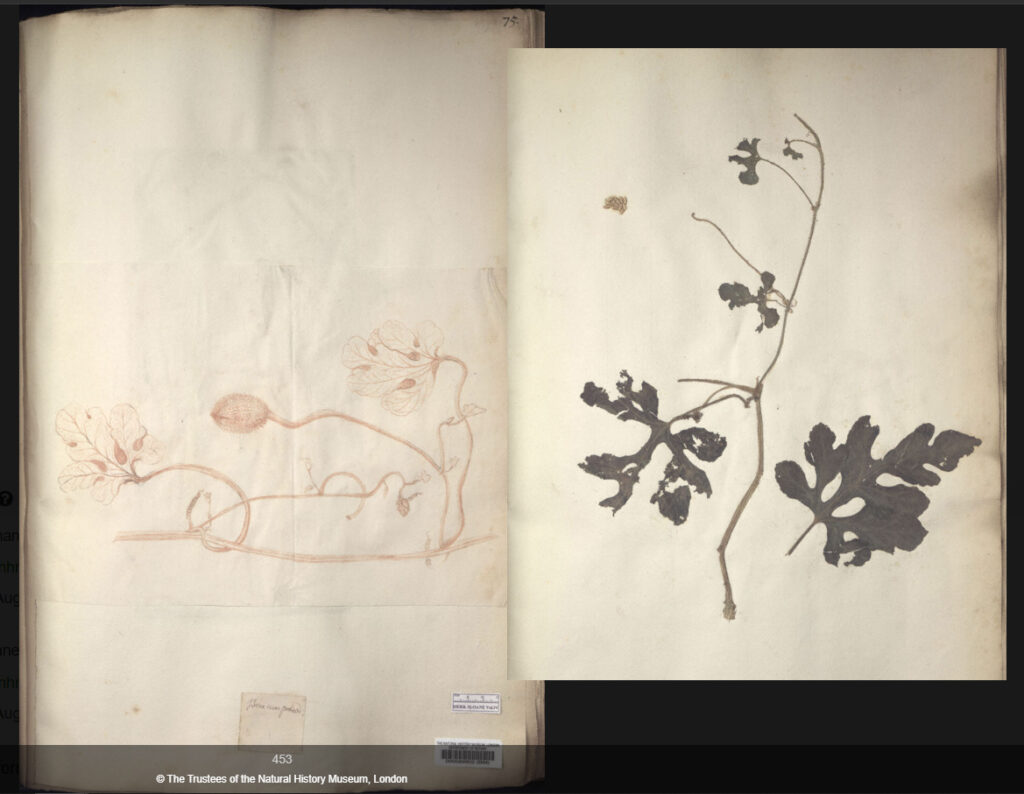

Regarding Cucumis anguria, these consist of a rather chewed up looking leaf, some seeds and a nice drawing. While in Jamaica, Sloane had addressed the problem of unpressable plant parts by enlisting the Reverend Garrett Moore to make drawings of them.

Neither of these two items eventually warranted an image in Sloane’s publications, but the species itself got an entry, as Linnaeus says, in the Catalogus of 1696. As it turns out, Sloane’s Catalogus is not very different from the Species Plantarum:

In general, just as in this entry for Cucumis anguria, it lists the polynomial of each species in his herbarium along with any prior references to the species that he’s aware of. For Cucumis anguria, these are:

- Marcgr. – which is Georg Marcgrave’s post-humous contribution to the Historia naturalis Brasiliae of 1648.

- Pis. (ed. 1658) – which is the 2nd edition of Historia naturalis Brasiliae, re-edited by Willem Piso in 1658 under the title of De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim, which was cited by Plukenet in the Almagestum Botanicum entry shown above.

- Pluk. tab. – which refers to the same plate 170 of Plukenet’s Phytographia, v.3 of 1692 which Linnaeus would reference later on.

Here, Sloane gives us an earlier reference not mentioned by Linnaeus or Plukenet, pushing the earliest publication date for Cucumis anguria back to 1648. Linnaeus was often quite selective with his references, even though he would have been aware of this one from consulting Sloane. We might speculate as to the reasons he left out Marcgrave in a moment. Several years after the Catalogus, Sloane published the first volume of A voyage to the islands Madera, Barbdos, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica. This was aimed at a more popular market so he took opportunity to say, in English, that he quite liked eating Cucumis anguria and that Piso didn’t know what he was talking about when he said it tasted bitter. Since he didn’t agree with that, he inevitably dismissed Piso’s little medical dissertation on pp. 264-265 of De Indiae in which he recommended against the use of Cucumis anguria on the grounds that it might be dangerous. Sloane also threw in another reference for good measure:

- Tournef. inst – which is Joseph Pitton de Tournefort’s Institutiones rei herbariae of 1719.

Nevertheless, it remains the case that the earliest of all these citations is Marcgrave’s in the Historia naturalis Brasiliae of 1648. Georg Marcgrave (or Marggraf) was from what is now Germany but was then the Electorate of Saxony in the Holy Roman Empire. He studied medicine and astronomy and in his late 30s, went to work for a Dutch trading company. He arrived in Dutch Brazil in 1638 with the aforementionedWillem Piso. The two of them seem to have been pretty much employed in researching the country and Marcgrave kept his notes in a secret code. This was surely not to preserve the anonymity of Cucumis anguria, but rather because he also took notes on geographical details and mineral resources which his employers might not want in the hands of their competitors. A few years later he died on a voyage off the coast of West Africa. It was Johannes de Laet, a Dutch researcher with a wide range of interests, who deciphered his notes and helped publish the natural history sections posthumously in the Historia naturalis Brasiliae, along with Piso who was still alive.

Marcgrave’s entry relating to Cucumis anguria is quite a short one, and in Latin:

My best translation, very much assisted by Google, is:

“Wild Cucumber of Brazil, creeps along the ground with a branching stem, the leaves are placed individually on long stalks, and are divided into three lacinia, with a toothed and hairy edge. The flower is yellow. The fruit is the size of a hen’s egg, elliptical in shape, with sharp tubercles all around, and pale when ripe. Inside, it contains many white seeds in a transverse position. It is edible.”

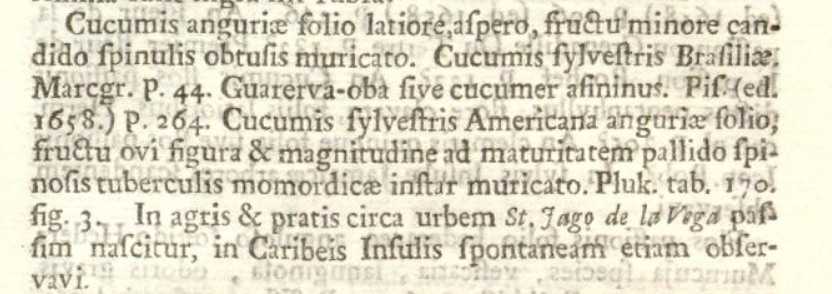

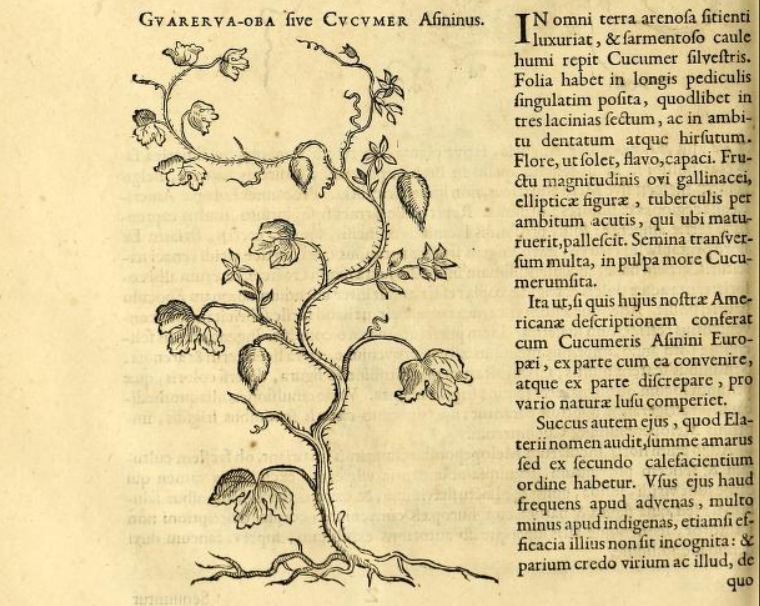

Marcgrave does not provide an image, nor any other information about the ‘wild cucumber’ in this short entry. Piso’s 2nd edition did include a picture:

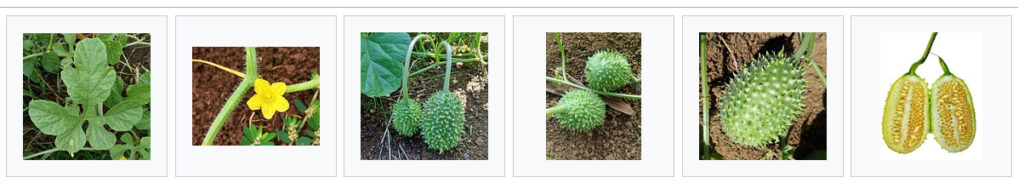

This is quite an attractive illustration, but as a source of botanical information it is over-stylised and might be misleading. Besides, it seems Piso was already starting to acquire a bad reputation as a plagiariser and fabricator of botanical information. These may be the reasons why Linnaeus, who lists the Historia naturalis Brasiliae in Species Plantarum on many occasions, overlooks both editions in favour of other authors on this one. Living as we do in the 21st century, we can supplement Marcgrave’s first description of Cucumis anguria with some photographs which show it to be pretty accurate:

Marcgrave does not cite any earlier references for Cucumis anguria, so as far as I know, the species was originally described and published in the Historia naturalis Brasiliae in 1648. By that time, it was naturalised in Brasil (and probably elsewhere), having arrived in the wake of the slave trade at some unknown earlier date during the preceding 150 years. European botanists presumed it to be an American plant although successive waves of slaves transported from Central West Africa surely recognised it on arrival. I would speculate that its presence in Africa was also already known to those Europeans, probably Portuguese in this case, who had been active in the plant’s African range since the late 15th century. However, if any of them wrote about it in such a way that it is recognisable, I’m not familiar with the reference.

So, that’s the publication history of Cucumis anguria, stretching back just over a hundred years before the Species Plantarum but connected to it by quite a short chain of citations. It includes a Latin description of the plant, an engraving, a more informal appreciation of its qualities as a food and a short dissertation on its suitability as a medicine. However, it’s very hazy indeed on the subject of its range and origin. Similarly, most (but not quite all) the species which Linnaeus listed in 1753 have publication histories.

Here is a little holding pen for instances of texts claiming, mistakenly, that Species Plantarum is a book of plant descriptions. Here we find the same issue as in Wikipedia, affecting the Encyclopaedia Britannica: